From Rubalcaba et al. (2019) American Naturalist 193:677-687.

Many ectotherms (cold-blooded animals like invertebrates, frogs or lizards) can control body temperature by exploting the thermal heterogeneity of the environment, for example, selecting sunny areas early in the morning, or moving to the shade or a burrow when it is too warm ourside. It is thought that this capacity for “behavioural thermoregulation” is being critical for ectotherms to buffer the impacts of climate warming.

It is important to measure or model the temperatures that organisms experience in each microhabitat. We use “operative temperatures”, defined as the equilibrium temperature of an individual in a microhabitat, to measure the repertoire of microclimates that individuals use for thermoregulation.

The operative temperature is the equilibrium temperature of an individual in a microenvironment, and depends on multiple heat transfer pathways, body size, shape and radiative proprieties of the animal.

But knowing the repertoire of operative temperatures is only part of the job. We also need to understand how individuals use these microhabitats to control body temperature throughout the day. For example, if lizards target a preferred temperature of 31ºC and they can select amongst basking sites (operative temperature 37ºC), shaded areas (26ºC) and burrows (21ºC), they will probably move between exposed and shaded areas to maintain body temperature near their preferred value.

Can we estimate the probability of use each microenvironment based on this information? and beyond that, can we model the probability distribution of body temperatures that individuals experience when moving among microhabitats? This is what we aimed here , applying the maximum entropy framework, a procedure to derive statistical distributions when we know little about the rules governing the behaviour of the system.

Using the maximum entropy framework to model behavioural thermoregulation sounds trickier than it is. This is why I’m writting this post (and this online app ).

Imagine that we know the temperature that a small lizard species targets in the field (we can just measure body temperature of individuals in the field to know that). Futhermore, we know the operative temperatures of each microhabitat (basking sites, shades and burrows) either because we measured them, or because we have a good biophysical model estimating these temperatures. We ask what is the probability of finding an animal in each site.

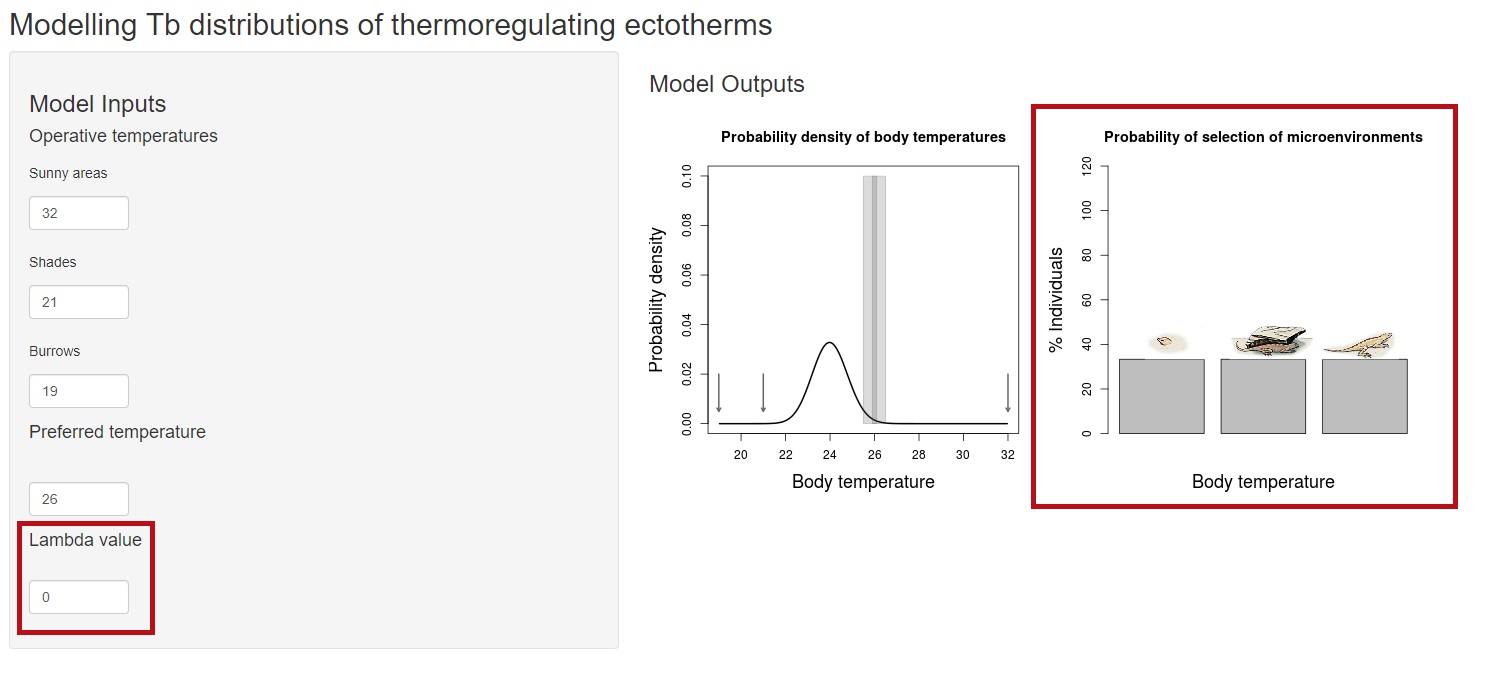

We may also need to know “how much they care” about experiencing body temperatures away from their preferred temperature, and how much variation are they willing to accept. If we talk about lizards, we know that many species are actually very good at controlling body temperature, while others act as thermoconformers. We therfore need a way to quantify how much thermoregulator is our species. This is what parameter lambda tells us. Although lambda can take any real value, we will just focus on values equal or lower than 0. When equal to 0, there is no constraint on the allocation of individuals among microhabitats, they will be distributed randomly:

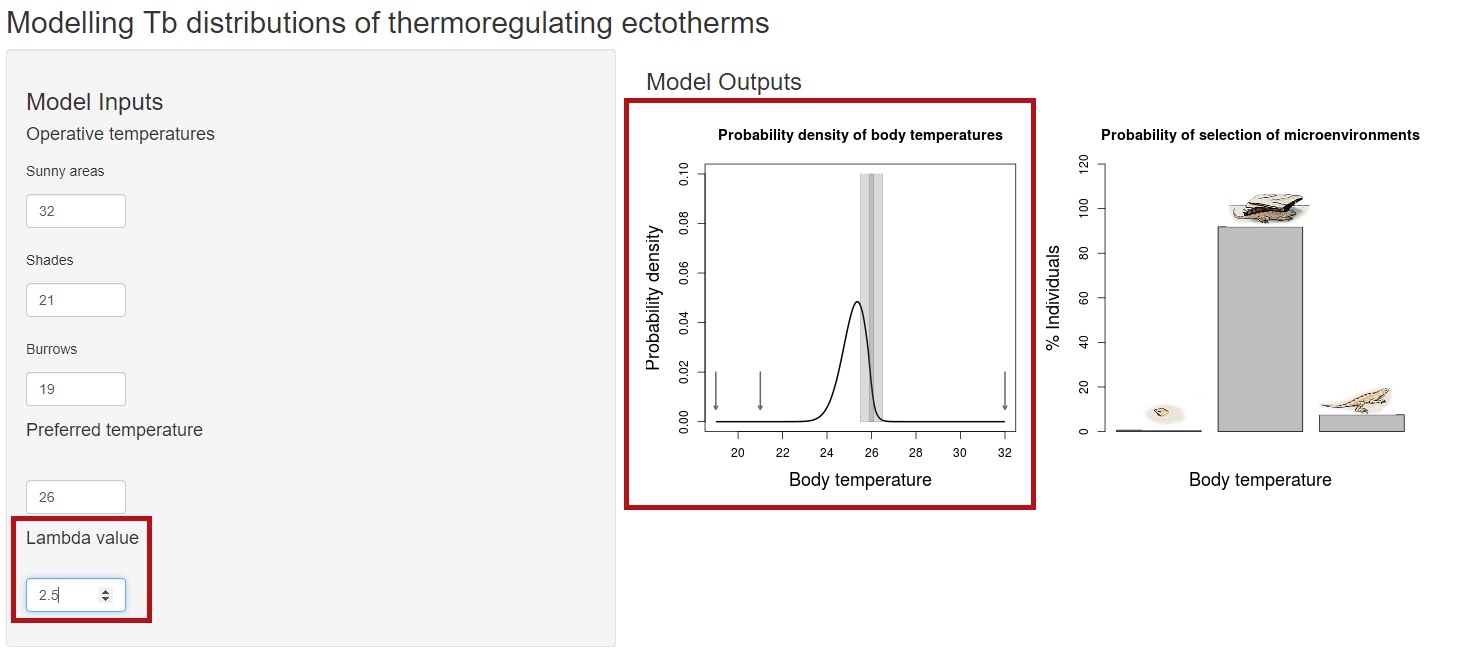

In this case, we are showing a very simplistic example where lambda = 0 means equal probability of sun, shade or burrow. But when individuals are randomly allocated they must sample the actual proportion of sunny areas, shades and burrows. The relative frequencies of microhabitats are prior probabilities in the model (here we assume a flat prior) and actually a topic for a further post. What happens if we increase lambda? values greater than 0 make the probability of selection of each microenvironment to be constrained by the preferred tempeature. Therefore, individuals will be no longer randomly distributed, but seeking for microenvironments that minimize the difference with their preferred temperature.

The next step is to model the actual distribution of body temperatures, the probability density function of a very large population of ectotherms thermoregulating in this repertoire of microhabitats. In fact, we can use demographic “integral projection models” to derive this distribution. We will need a transient-heat model to calculate the probability that body temperature changes a given amount in a given microhabitat (e.g., increases 2ºC in the sun), conditioned by the current temperature of the animal, and the probability of selection of this microhabitat. In this case, I used a very simple transient-heat model to simulate changes in body temperature in relation to time and microhabitat for a small 5g lizard.

So what is this model for? There are two main questions that we can address with this model. First, when we know the repertoire of operative temperatures, modelling the distribution of body temperatures gives us information about what is the probability that animals experience, for example, temperatures above their heat tolerance limit, and how effective will be to improve behavioural strategies for thermorregulation. Second, our paper shows how to contrast predicted distributions with observed body temperature data. With this information, we can derive the actual value of lambda (the thermoregulatory strategy) displayed by our population. This measure informs about the potential of behaviour to buffer climate change.

There is a lot of questions that we can address and see how the model behaves with other species in different regions. I hope this model will provide insights into the responses of ectotherms to climate warming.

Juan G. Rubalcaba