Extracting oxygen from the environment -to generate energy for locomotion, growth and reproduction, is especially challenging for aquatic animals because the availability and diffusive capacity of oxygen is much lower in water than in air.

Contrary to warm-blooded animals such as mammals and birds, cold-blooded animals like fish increase their metabolic demand for oxygen as temperature increases. In a warming world, many fish species would experience higher metabolic rates, and therefore, they need to increase oxygen supply rates to meet this demand. However, respiratory organs (gills) and circulatory systems of fish cannot extract and distribute oxygen to tissues at an infinitely high rate. If oxygen supply doesn’t meet demand in warming waters, fish may experience lower survival, reduced growth rates, or may be forced to migrate toward colder latitudes.

There is little consensus as to whether fish would experience oxygen limitation in warming waters. This lack of consensus is, in part, due to the fact that we don’t have models to calculate maximum oxygen supply rates of respiratory organs of animals. One of the most important models that ecologists use to calculate how metabolic rates change with temperature and scale with body mass is Metabolic Theory of Ecology (MTE). According to this theory, metabolic rates increase with temperature in an exponential way (the Arrhenius-Boltzmann equation), and scale with body mass as \(\propto M^{3/4}\) However, MTE does not include oxygen supply rates, which is equivalent to say that it assumes that oxygen availability is always high enough to meet demand. Although this assumption is valid for resting, terrestrial organisms, it may not represent most aquatic animals.

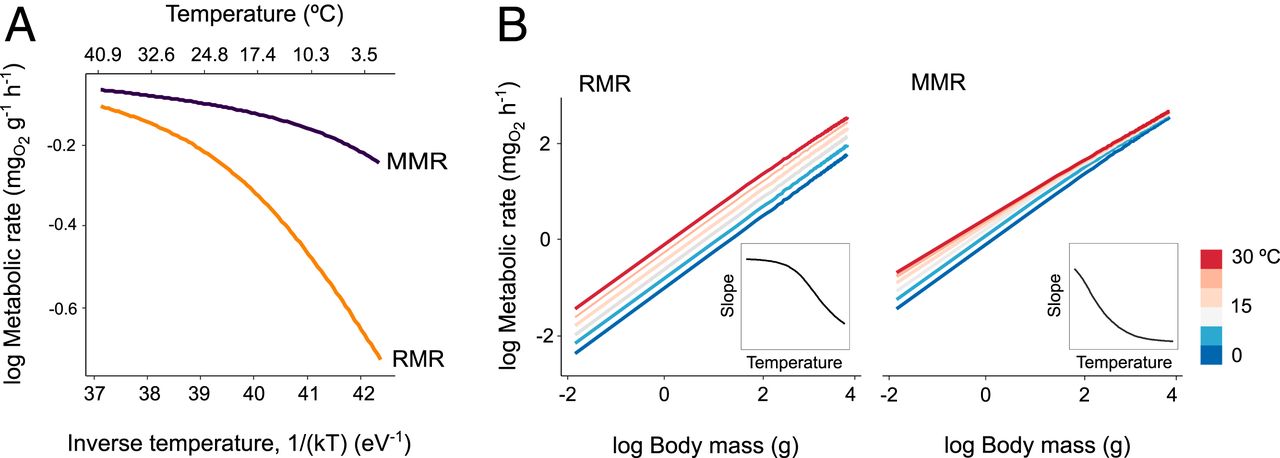

We introduced oxygen supply into MTE and found that oxygen availability determines both the relationship between metabolic rate and temperature, and the scaling of metabolic rate with body mass. Thus, while MTE predicts that the slope of the temperature dependent relationship is constant (~0.6 eV), the value this slope should decrease under oxygen limitation. Similarly, while MTE predicts that metabolic rates scales as 3/4 times (log) body mass, oxygen limitation also reduces this mass-scaling slope.

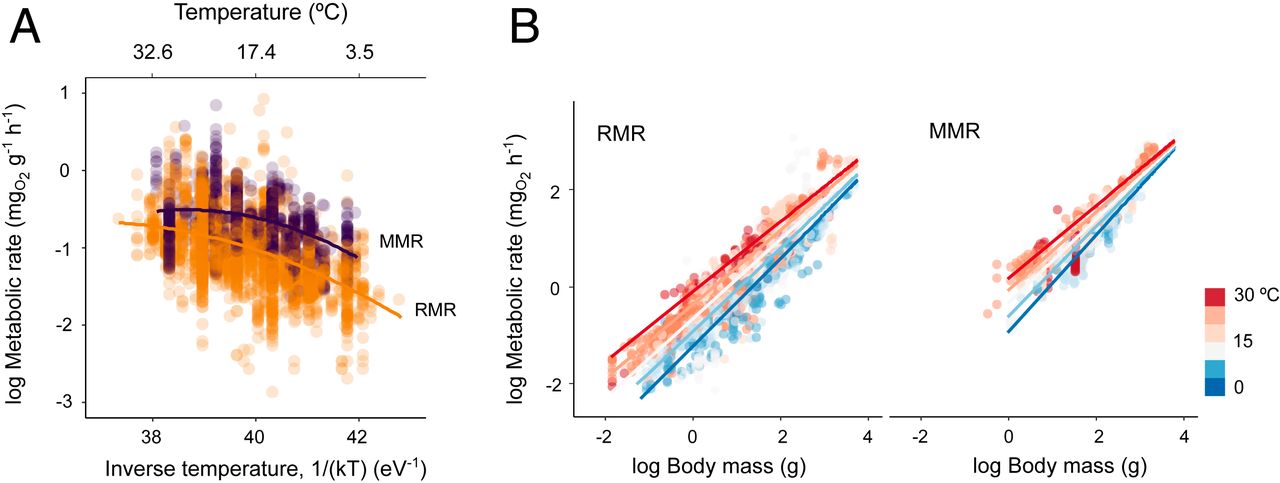

So the temperature and size dependence of metabolism change due to oxygen limitation, but does it have any implication? We can use this result to investigate, empirically, if oxygen limitation affects fish metabolism. Many empirical studies have measured metabolic rates of differently sized fish at different water temperatures, and compared resting fish (resting metabolic rates, RMR) and active fish (maximum metabolic rates, MMR). We just had to collect these data (which include thousands of measurements across more than 200 fish species) and see if the empirical relationships metabolic rate vs temperature, metabolic rate vs body size, match our model’s predictions.

To do this, we made our predictions comparable with empirical data: (1) our model predicts that oxygen limitation reduces the slope of the relationship metabolic rate vs temperature, so we expect that MMR (more oxygen limited because fish are active) increase with temperature at a smaller slope than RMR. (2) the model predicts that oxygen limitation reduces the slope of the mass-scaling relationship, so we expect that the mass-scaling slope decreases at warmer temperatures, especially when the activity level is high (MMR).

These predictions can be directly compared against empirical data:

The model and data together suggest that oxygen limitation determines how metabolic rates change with temperature and body mass. Of course, similarity between observed and predicted patterns doesn’t mean that oxygen limitation is the ultimate mechanism driving the empirical results. Our model does not reflect an underpinning law that all fish must obey, because biological systems are complex, evolve, and respond to environmental changes. Instead, the model allows us to hypothesize about the effect of oxygen limitation on metabolism, and make predictions that would be difficult to present and explain with a verbal model. Morevoer, the model provides a means to experiment with parameters that represent actual mechanisms involved in fish respiration. We can, for example, answer questions such as “how much should fish ventilate their gills to mitigate oxygen limitation?” or “can fish avoid suffocation by reducing their activity levels?” -otherwise impossible to address using traditional correlational approaches.

Our study demonstrates that warming waters can cause respiratory distress in fish (especially in larger individuals), even when compensatory mechanisms are taken into consideration. We encourage further experimental research to understand the impact of oxygen limitation on fish physiology, behavior and survival.

Juan G. Rubalcaba

Dec 2, 2020